Today you will…

...Take part in activities to help you understand the level of medical knowledge and training available to medieval physicians understand levels of change and continuity in medieval medicine understand which factors influenced medical knowledge and expertise in this period be able to access and analyse primary source material.

As part of the GCSE medicine course 1 in history, because little progress is made in the western world, the medieval period could be glossed over fairly quickly – yet this is a fascinating era with some great primary source materials. This lesson aims to help students gain a practical understanding of the levels of medical knowledge in the medieval period, and levels of change and development from what came before it and in the context of the time. It could work either following learning about the bubonic plague or act as a precursor, and fits well as part of series of learning sessions taking in a larger assessment of the effectiveness of different aspects of medieval medicine, following an initial introduction to some of the main concepts. Most of the images and written information can be accessed from the British Library’s Medieval Realms resource (tinyurl.com/clve2h5) or from the British Library Timeline (bl.uk/timeline). As they continue into the lesson, students will gain an understanding of which factors affected the development of their medical knowledge.

Starter activity

‘Trust me…i’m a physician’

Set the scene and share this quote written by the Italian poet Petrarch (1304-74) who was writing to the Pope: “I know that your bedside is besieged by doctors, and of course this fills me with fear. As Pliny said, in order to gain fame they buy it with our lives. They learn their art at our cost, and even our death brings them experience; only a doctor can kill without punishment. Remember what it says on the gravestones: ‘I died of too many doctors’.” What does this suggest about the knowledge, training and reputation of medieval physicians?

Explain to the class that it is their job to test out whether Petrarch is right to mistrust physicians. Explain that the class will become western medieval physicians and will have access to the latest medical knowledge in order to treat their patients.

Main activities

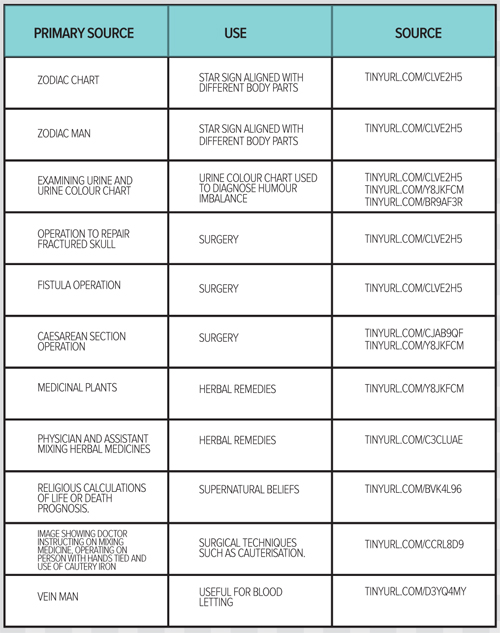

1. Morning surgery

Students are in small groups. Source materials are given to each group. These can be printed out, or each group could be given the links to resources online through an electronic book that the teacher has pulled together. Depending on the ability range of the students and the previous level of introduction to medieval medicine, the treatise can be structured so as to provide explanations and recommendations alongside the sources. Suggested primary source images are listed in the table overleaf. This will form their medical treatise. Suggestions given are not an exhaustive list of the ailments and treatments of the period, but will give students a flavour. Explain to students that as medieval physicians, the information they need to treat their patients for this morning’s surgery will be in their treatise, although they may also need to ask the patient some questions. Hand out the dirtiest aprons on loan from the science department that you can find! Patient cards and props will also be handed out to each group giving details of the patients’ characters and their symptoms. It depends how far you wish to go, but props can include test-tubes filled with apple juice and cold black tea, fake blood, fat liquorice sticks and large black circular stickers for example.

2. Appointment time

p>p>The patient of the group is the only person to travel. For each different ailment, they must visit a different doctor. It is the job of the medieval doctor/s to find a source that they think correlates to the ailment and to recommend a course of treatment to the patient based upon the information in the source and what the treatise tells them.

All of the information should be recorded by the doctors’ assistant/s and a prescription written. The doctor’s assistant is in training and can make suggestions too. According to John of Ardennes, a physician should not take less than 100 shillings (£200) for the cure of a sickness. Based on the treatment given and the context of the time, the patient should decide how much to pay the doctor. A fair price must be reached based upon the following:

• Would the treatment have worked or been effective? Or would it have resulted in death?

• Was the right treatment for the time recommended? Would one of the other treatments on offer have worked better?

• Would further complications have arisen as a result?

• Was the treatment anything new? Did it represent the latest medical thinking?

• Was the treatment tried and tested in the past and therefore trusted? Or could it have been considered an outdated idea?

Give a competitive edge to this task– the winning group has the greatest amount of money at the end of the task, although many will find they are fighting a losing battle!

3. Feedback…

There are various ways of managing feedback; for example, it could be done through getting students to take it in turns to perform each roleplay situation, or by means of a whole class discussion. Get the class to build up a list of possible treatments that medieval doctors would have had at their disposal as well as which treatments represented change and which represented continuity from previous periods. Discussion can also be made as to the balance of natural and supernatural treatments and how this compares to previous periods. Students should be led towards an examination of levels of progress. This information could be reflected in a piece of writing or a chart.

Home learning

• Find out about medieval public health and the Black Death or medieval surgery if this lesson precedes learning on that topic.

• Ask students to find out more about medicine in the Islamic world in the Middle Ages, particularly Ibn Nafis, Avicenna, Constantine the African and the medical school at Salerno. How did medical progress in the Islamic world compare to the west? Prepare a treatise according to Islamic ideas.

• A written piece on change and continuity in treatments and cures from the Roman period to the end of the Middle Ages.

Summary

Remind students of the initial question – was Petrarch right to distrust medieval doctors? The class should be able now to point to issues of levels of knowledge and training, but should also be able to put this into the context of medical knowledge at the time.

Which factors affected the levels of progress at this time? GCSE history students following the medicine course should be familiar with the main factors that affected the progress of medicine by now. It is up to the teacher how to carry out this activity; I like to play the factors game. Remaining in groups, students are given their set of factors cards (that we have been using throughout the course). Students buzz in with the factor/s and accrue points, as long as they can explain how the factor is at play. Alternatively students could remain in their groups and be given one factor to prepare an argument for as being the most important at play.

Info bar

Additional resources

• tinyurl.com/bsz9ypa podcast on how effective medieval medicine was. tinyurl.com/cck98ds gcse bitesize on medieval medical knowledge, with video and test.

Stretch them further

• Try giving students less structure – can they work out how the zodiac chart was used? Can they decide what the different urine chart colours meant in accordance with the body’s humours? Can patients think of their own criteria for deciding payment?

• Can students find other examples of medieval treatments not found in the treatise? e.g. flagellation? Does this new evidence change their previous conclusions?

• Try getting students to find examples of progress in medieval medical practice. where does this usually occur? Why?

About the expert

Mel Jones is very lucky in her role that she gets to work with experts in history education, teachers and students alike. Mel likes nothing more than seeing the students get a buzz from what they do through enquiry and interrogating primary sources. A lesson that is talked about a long time after the event is a lesson remembered.