It seemed so simple in the post-war years: 'bright' children were destined for grammar schools and professional careers, and the 'less able' were destined for secondary moderns and vocational futures in the trades. Comprehensives, in turn, aimed to service all abilities, and 'differentiation' was the buzzword. Whilst accusations flew to and fro about whether or not these systems were 'elitist and discriminatory' or 'failing to stretch the ablest', the notion of 'ability' was rarely questioned. Few wondered whether the concept itself might need updating.

Towards the end of the 20th century the term 'gifted and talented' entered the formal vocabulary of English schools, first through the Excellence in Cities Programme and then through a welter of emerging national structures and 'G&T' initiatives – many of which have now morphed into the 'personalised learning' and 'narrowing the gap' agendas.

Carpe diem – seize the day! We now have the opportunity to take G&T away from the mean streets and dead ends of 'ability', 'identification' and 'cohorts' and turn instead into the open avenues of learning and gift-creation for all.

So what exactly do we mean when we label someone as 'gifted' and how do we decide who is? Do we need to? There are hundreds of definitions of giftedness, but since labels lead our thinking as well as describe it, let's give some serious thought to a couple of these. First, a very familiar one:

• Exceptional academic ability or potential relative to one's peer group.

And a related way of 'reading' Safia, a Year 7 pupil:

• It's no wonder Safia's so bright. Her parents are both highly able people themselves. Her exceptional academic achievements are explained by her natural giftedness. She clearly needs special provision, and she has in fact responded well to the accelerated literacy and numeracy provision she's had access to as part of her primary school's G&T cohort. She's one of their success stories and is destined for great things.

Now consider this, less familiar definition of giftedness:

• A preparedness to invest time, energy and resources (intellectual, physical, emotional, social) into an area of learning. And a related 'reading' of Safia:

• Safia has responded tremendously well to her stimulating and supportive home background and to the opportunities she's had in school. She's achieving wonderfully well but is showing signs of being more interested in her scores and class position than in her learning, and she's nervous of 'failure'. She seems, however, to have a genuine interest in art and design – how might I best help her to deepen and extend her interest in this area?

Which of these definitions and 'readings' do you hear most often in the staffroom. Which do you feel most comfortable with? Why? The first has one huge pro: it's comfortably familiar. It's so steeped in our national psyche that it barely needs stating. Some kids are just brighter than others, and the very brightest are gifted. Period.

The problem with this norm-referenced definition is that despite the frequency of their use, no one can claim definitively to know just what the terms 'brightness', 'ability', 'potential', 'intelligence', 'cleverness', 'giftedness' etc. actually mean. We may think we know what they mean. They might share some family resemblances, but they are tools, not essences. And whilst we might believe we can measure them through IQ tests and the like, we have no widely accepted understanding as to what exactly 'them' is.

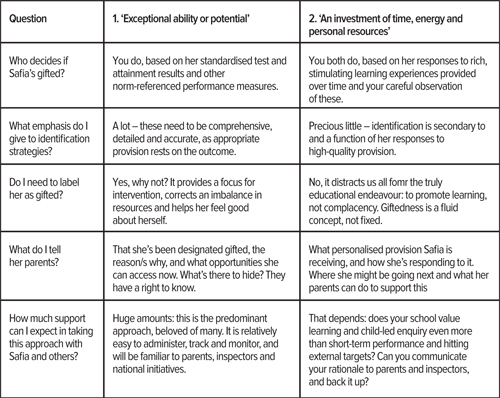

Definition 2 has the big pro of being related to the learning of the individual, not to any comparison group. Moreover, it needs no big brother concept like 'ability', 'potential' or 'intelligence' to make sense of it. Its con? We can't easily measure it. And if that's the case, can it have value in our education system? The two different definitions of 'giftedness' lead to contrasting responses to questions you, as her teacher, might be asked about Safia, or any other child, as in the table below:

Professor Carol Dweck, a developmental psychologist from America, has spent the best part of 40 years studying factors that support and inhibit learning and achievement. She describes intrinsic motivation (that hunger to learn that comes from within the learner) as the 'motor of intelligence' – but remains agnostic as to what exactly intelligence is.

Carol Dweck and her colleagues have found that:

• If you believe something to be an inherent, fixed quality (e.g. fixed ability, giftedness, intelligence), then in the face of difficulties you're more likely to grumble, crumple or cheat!

• If you believe something to be learnable (e.g. seeing ability, giftedness, intelligence as 'growable'), then in the face of difficulties you're more likely to try harder, develop new strategies etc – and therefore become better at it.

• We're fairly evenly split over things like intelligence, ability etc. About 40% of us incline towards 'fixed' beliefs, and 40% towards 'malleable' beliefs. The rest of us swing from one to the other, dependent on the domain, eg holding fixed beliefs about our 'maths ability', but malleable ones about our DIY skills.

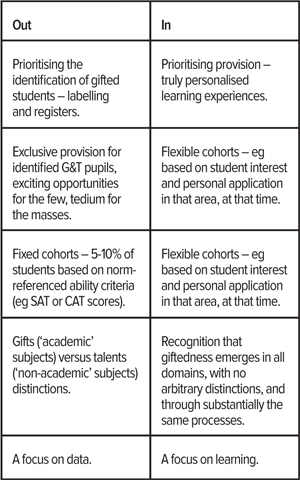

• Highly successful people are much more likely to believe that they can always improve – and work hard to do so. Believing in the plasticity of giftedness and the importance of promoting intrinsic learning motivation has implications for school and classroom practice. So what's 'in', and what's 'out'?

"What you really need is stick-to-it-iveness. It's a noun. It means dogged persistence. This is what I was taught. I was dylexic, the least likely to succeed. It means things don't just happen – you have to make them happen."

Erin Brockovich, campaigner

"Talent is not enough"

Martin Jol, football manager

"If people knew how hard I had to work to achieve my mastery, it wouldn't seem wonderful at all."

Michelangelo

"Greatness is not given. It has to be earned."

Barack Obama, US President

About the expert

Dr Barry Hymer is the Osiris Professor of Psychology in Education at the University of Cumbria. He is the author or editor of seven books and numerous papers in the fields of gifted education and thinking skills, including Gifted and Talented Pocketbook (teachers pocketbooks, £7.99, available directly from teacherspocketbooks.co.uk, 0800 028 6217), from which this feature has been adapted.