IF OUR AIM IS TO DEVELOP A CULTURE OF LOVING TO LEARN IN OUR SCHOOLS, THEN WE NEED TO UNDERSTAND WHAT YOUNG PEOPLE REALLY WANT AND NEED, SAYS CEO OF NAACE MARK CHAMBERS...

Not every school is the same. It’s an obvious statement, but as we focus increasingly on educational outcomes it’s important not only to acknowledge this but to examine the differences. Some schools have levels of engagement that are significantly better than other schools; you can see from the current television programme ‘Educating Yorkshire’, just how much effort schools are putting in to get their pupils to achieve, and how successful they can be. But some schools appear to have achieved a qualitative difference in the way that their pupils are engaging, with a big improvement in their attitudes to learning.

Looking into this difference is critical. To get a step-change increase in learning there must be a mechanism. Over the years, many case studies and research reports have shown that, under certain circumstances, the learning and achievement of young people can progress much faster than the average.

When this is noted and discussed in political or Ofsted circles it tends to be expressed as the need to have high expectations and for school leaders to ensure an environment that is conducive to learning – but this does not go into enough detail.

In Naace we have seen evidence that points to a change in the communal and individual attitudes of pupils as a key mechanism. It should be no surprise that this shift in attitude results in them using time in lessons in a more concentrated and productive manner. But what is the change driven by?

A culture of learning

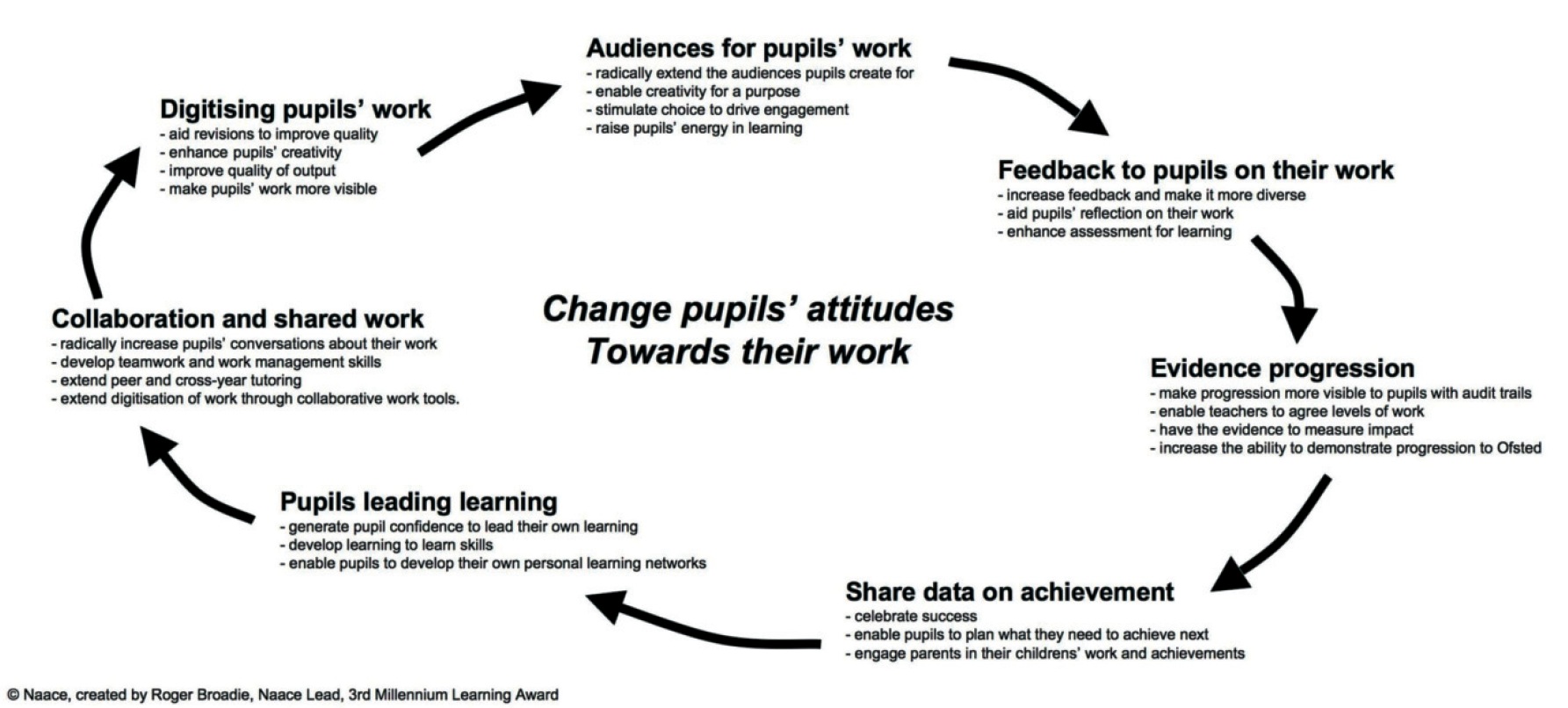

Promoting a culture in the school where more positive attitudes can develop is key. This change in attitude must come from the young people themselves, and from the evidence that we’ve seen, we believe that the schools achieving this are implementing a ‘virtuous spiral’ that stimulates students to want to learn much more strongly. The use of technology is a key catalyst; not for its own sake but because it is so powerful in enabling the elements of this virtuous spiral (see diagram, above).

There is no right place to begin for a school, although identifying strengths and bottlenecks that stop improved attitudes from spiralling upwards is a useful exercise. A common starting point is using technology to digitise pupils’ work, and introducing online systems to make that work much more visible. In a society where technology permeates so much of what children and young people do, this is more important than many of us may realise.

Making pupils’ work digital is not just about work done on computers. Images can be taken of all sorts of work using tablets, phones or visualisers. These images can then be posted on class or school blogs or in the submission and assessment systems of online platforms or virtual learning environments (VLEs). We could look at this as the educational equivalent of the traditional “Mark and Roger were here” type of graffiti; if it is oddly satisfying for young people to see the evidence of their place in time then naturally it’s motivating to see the evidence of their work, and of their progression.

Share and develop

The next step is audiences. The first audience is the teacher but many are now introducing peer tutoring, identified by the Sutton Trust/Education Endowment Foundation as a “high impact” approach. With online systems, the peer collaboration and tutoring is not restricted to the classroom. Audiences can be extended; parents still matter to pupils in secondary schools but other peer and adult audiences can be incredibly useful. There is little more motivating than someone you have never met praising your work. Schools are using assemblies, digital signage, activities and projects to provide reasons to get audiences looking and commenting. They are creating their own school radio stations and TV channels that provide outlets for pupils’ creative work and get them talking about it as well. This takes pupils’ work into a new arena. All of a sudden, it’s not just being done for the teacher, but for a wider purpose.

The feedback part of the cycle is where the value discussions happen, in fact it’s also one of the high impact approaches identified in the Sutton Trust/Education Endowment Foundation meta-study. Technology has a strong role to play here too, as it captures feedback more effectively. Praise from a teacher makes us feel good, but praise captured in an audit trail of reflections and comments can have lasting impact, making pupils feel good about their achievements and even failures.

Evidencing progression means that pupils come to see not only that their work is good, but that their achievements have a wider value. They come to see how the work that is accumulating in their digital portfolio is taking them towards real goals. Because digital systems make it easy to call up work done a considerable time ago, the emphasis can change from looking at current achievement to seeing progress. Even if current achievement is not high in relation to their peers, pupils can see their own personal journey and how far they have come.

Once these attitudes develop, admitting that we currently cannot do certain things becomes a lot easier, and it becomes possible to share data on pupils’ achievement more widely, with parents and with their peers. Ultimately, the question is not what a pupil can and cannot do, but what the most helpful next step in learning is for him or her.

Learning from learners

Pupils leading learning is seen in all the schools that have gained the Naace 3rd Millennium Learning Award. There are sometimes groups of students leading in certain areas, such as learning about technology or e-safety, but it is also seen across the curriculum where more collaborative approaches are being developed.

The tools that technology provides are often at the centre of the collaborative work. We see pupils working together in Google Docs or Microsoft 365. We see them creating video revision materials for each other and using audio files. One school commented that behaviour on the school buses has improved considerably since pupils started to make use of their own technology to access learning resources online.

Behind the whole of this virtuous spiral is one key factor supported by one enabler. The key factor is that pupils are being encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning and for helping others learn. The key enabler for this is technology. It is giving pupils access to learning opportunities and tools and it is giving them the ability to exercise personal choice about how they work and how they structure their learning. The videos produced by schools for the Naace 3rd Millennium Learning Award show what can happen when pupils take ownership of the process of learning and want to do it.

Our worry is that there are still schools that are failing to look at what is happening, often in establishments just down the road; they are failing to acknowledge that pupils have personal devices and Internet access and are locking down systems in school, denying the kinds of choices that are driving the improved attitudes to learning in their neighbouring schools. Our young people are going out into a connected world where they will need to learn at every moment in their lives and where their exposure to technology won’t be limited. It’s our job as schools and parents to make sure they’re prepared.

It’s important that schools engage in the same sort of peer to peer development that has proven so successful with learners. Learning doesn’t stop when we become adults, especially not in a world where technology evolves at such a blistering rate.