Integrity is all very well – but not if it’s a personal luxury enjoyed at the expense of your students’ achievements, warns Phil Beadle…

It was my privilege on the day before the Easter holidays to deliver some ‘Literacy Across the Curriculum’ training in a school in seaside Essex; an establishment that struck me as one of the most functional, healthy places I’ve ever visited: the walls strewn with lovely, intelligent work; and a set of teachers who clearly adored each other and heartily enjoyed their many friendships. (I even got a cuddle from one as a way of saying thank you for the session. Which is a first.)

The staff spoke as one about the place: they loved working there, and all expressed admiration, respect and affection for the head teacher. So impressed was I that I momentarily considered moving my family immediately to Essex to have all three of my kids educated at such an emotionally functional place. My wife, equally immediately, nixed the idea. I had a chat with the head and shared my observations. Despite her obvious pride in the place, despite her clear personal charm, she was clearly carrying a worry on behalf of the community: they’d taken a hit from the AQA grade-stealing debacle, and would not be getting outstanding again in their imminent Ofsted. Furthermore, they were now dangerously close to the floor targets (!) Her concern was that her own integrity had made the community’s future (at least mildly) problematic. “We’ve always felt it important that the kids get the grades that they deserve,” she said. It is a testament to that head teacher’s integrity, and to my own lack of the same, that my first thought was, “How quaint! ‘Kids get the grades that they deserve.’ What a charming, antiquated notion.”

One of the (many) things I do for a living is go into schools and play a role in rescuing English results. Generally, the problems in struggling institutions are the same: lack of understanding of what the kids might actually be capable of if you push them; unintelligent, slavishly obedient task setting; no one having thought it might be a good idea to teach basic skills; and, finally, and most crucially, fear of the demon examiner telling you that you may never work again. This fear manifests itself in taking the rules as things to be obeyed as opposed to things not to break. This is the chief principle of effective ‘gaming: you work within the letter of the law but outside of the spirit. Wanna know how the academy chains report exponential rises in achievement? The answer is in the second clause of the second sentence of this paragraph.

As a consultant this approach often causes me to brush up against teachers’ sense of their own professional integrity as being inviolable. My stock answer to this is that a teacher’s notion of his or her own integrity is a vanity, and if it is a vanity that causes a single working class child to fail to achieve the grades that would otherwise get him or her into university, then it’s an untenable and borderline immoral one. Integrity is also a moveable feast. One teacher’s slavish adherence to the rules is another’s flagrant gaming. ‘Integritier than thou’ seems to rule many roosts, and those most proud of their record in this regard seem also perversely proud of having failed legions of students, as their ‘integrity’ wouldn’t let them go the extra mile. Furthermore, integrity is a continuum. Obviously, most adhere; but I’ve heard tell of one head of a very successful department’s response to the introduction of controlled assessments, which was to completely ignore them, and to continue redrafting. She is yet to rouse even the merest of suggestions of light suspicion from exam boards.

There have been considered and reasoned arguments to make doping in sport legal. If everyone’s doing it, then making it legal at least ensures that there is a level playing field. What we have with the current league-table-driven remorseless and relentless focus on results alone is a situation where a friend of mine can state quite emphatically, “Look, Phil, in a system that is entirely without integrity, the person who hangs on to his is a fool,” and find me nodding. Guiltily. But not very. Hang onto yours at your own risk.

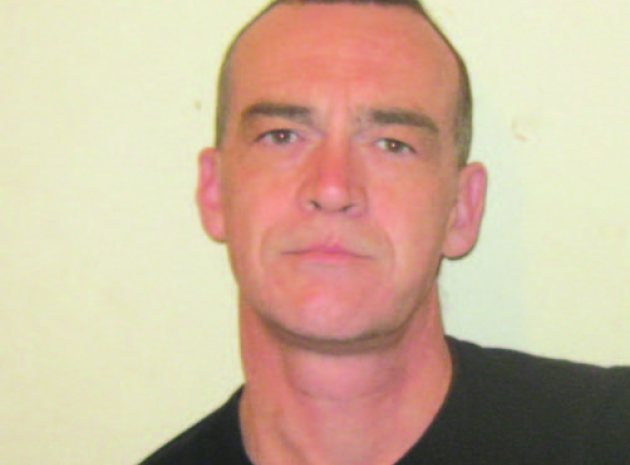

Phil Beadle is an experienced teacher, author, broadcaster, speaker, and journalist. (philbeadle.com).

“It is a testament to that head teacher’s integrity, and to my own lack of the same, that my first thought was, “How quaint! ‘Kids get the grades that they deserve.’ What a charming, antiquated notion.”

Integrity is all very well – but not if it’s a personal luxury enjoyed at the expense of your students’ achievements, warns Phil Beadle…