In the first of a new series considering lessons he’s learnt from lessons he’s taught, David Didau looks at ways to plan more effectively...

As a new teacher, lesson planning seemed to suck up almost all of my available time and energy. Looking back over those frenetic early years it’s become increasingly clear that I wasted an awful lot of effort thinking about what my students would do rather than what they would learn. What, I started to wonder, if I were to spend more of my time on those parts of my job that have the most impact and stop bothering with the guff? Well, in my increasingly obsessive quest for efficiency, I’ve arrived at the five (fairly obvious) planning principles below...

1. Time is precious

Instead of planning individual lessons, I want to invest my time in the medium term planning to break down the skills and knowledge students will need to learn to arrive at their destination. There may be all sorts of really efficient ways to give feedback during lessons, but for me nothing beats marking their books. Sitting on a pile of unmarked work for weeks is useless though – to have impact it needs turning around as quickly as possible. If I can set up lessons so that I’m marking while the students work, then so much the better. But when that’s not possible I need to make sure that any time I have available is spent marking, not cutting out card sort activities.

2. Marking is planning

Time spent marking students’ work should be time spent working out whether they can do what you think they can and what they need to do next. Instead of just writing comments, I ask individual questions, and set focused tasks for them to complete. And the trick to this succeeding is to dedicate lesson time for learners to complete these tasks. For a year 7 class it might be reasonable for them to spend 10 – 15 minutes acting on feedback, but my A level classes will often spend a full hour improving essays.

3. Focus on learning not activities

Loading lessons with things to do actively gets in the way of students learning whatever your clear, thoughtful objective was. It’s no good planning engaging activities that distract students from thinking about the essential point you want them to learn. Ask yourself, what will students think about during the lesson? What they think about is what they will learn. I recently watched a lesson in which a teacher wanted her class to think about the lives of Irish peasants during the Potato Famine and hit upon the idea of hiding potatoes around the classroom. The students loved it. They came up with great hiding places and learnt a lot about where you can conceal a potato in a small room. They did not learn much about the lives of Irish peasants.

4. Know your students

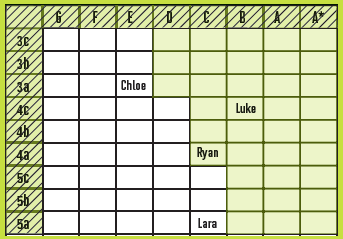

This sounds insultingly obvious but is easily forgotten. It’s a widely accepted truism that good teaching is founded on good relationships. Good relationships are, in their turn, founded on detailed knowledge and understanding of the kids you teach. Knowing your students makes you bullet proof. Make sure you know their data as well as the narratives that underpin it. Using a transition matrix like the one below can help:

5. The ‘1 in 4’ Rule

Let’s be realistic, churning out Outstanding TM lessons five or six times a day, every day is unsustainable. Working yourself into the ground benefits no one. In any given week I’ll spend a disproportionate of my planning time on one or two lessons, but most will be put together in five minutes or less. My formula is that if every fourth lesson for every class is a corker, all will be well. And if a lesson’s worth its salt it ought to produce work that is marked and then becomes next lesson’s menu anyway.

Armed with these guiding principles, planning individual lessons is now reduced to addressing the following questions:

- How will last lesson relate to this lesson?

- Which students do I need to consider in this particular lesson?

- What will students do the moment they arrive in the classroom?

- What are they learning, and what will they think about during the lesson?

- How will I (and they) know whether they are making progress?

So, these are the lessons I’ve learned about planning lessons. Although underpinned by years of bitter experience, they are, of course, just my thoughts. Why not share yours on Twitter (@TeachSecondary; @LearningSpy)?

David is an associate of independent thinking and has run two english departments and been an assistant head with responsibility for teaching & learning. he is the author of the best-selling ‘The Perfect English Lesson’ and his new book, ‘The Secret of Literacy’, is out in January 2014.

In the first of a new series considering lessons he’s learnt from lessons he’s taught, David Didau looks at ways to plan more effectively...